The Granite Industry of Bohuslän

In the 1800s, Europe saw fast population growth, urbanization and industrialization. This led to more trade and a need for better transport. Old cities were crowded and dirty, diseases like cholera spread easily. Shaped granite became very important during this time.

In northern Bohuslän, granite was cut for streets, roads, harbors, bridges and buildings.

Clean stone-paved streets replaced muddy ones. New deep harbors helped trade grow and stone roads made land transport easier.

In the mid-1800s, early quarries were small. All work, from breaking the rock to making paving stones was done on site. A stonemason could work alone or for a company, using simple hand tools like hammers, bars and pulleys, much like in ancient times.

By the late 1800s, new tools like dynamite, drills and grinders changed the work.

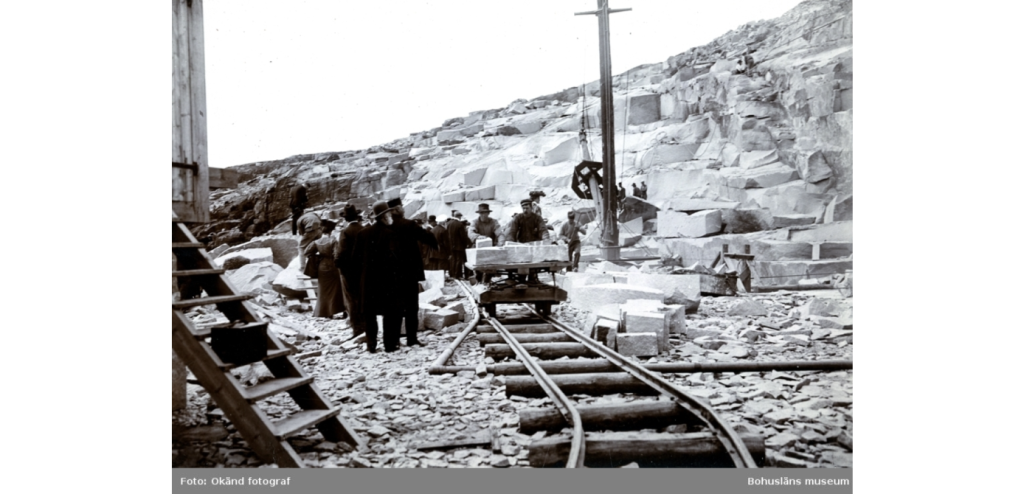

Around 1900, large quarries were created along the Bohuslän coast. Granite blocks were now transported to special workshops for shaping into paving stones or gravestones.

The work became more organized with fewer but larger quarries. Machines like rail tracks, steam cranes and larger docks made the industry more efficient. New job roles appeared, from quarry workers to ship loaders.

A Quarry is a place where rocks, sand or minerals are extracted from the surface of Earth.

Stonemason – A person whose job is to cut and/or prepare stone.

Lahälla – A Granite Community

Lahälla, in Brastad Lysekil Municipality, is one of many small communities that grew around the granite industry. The quarry at Lahälla opened in the early 1880s. At first, it was called Bräcke Stonemasonry and was owned by a businessman named Nielsen from Gothenburg.

Later, it became a limited company.

The quarry is located high above Brofjorden. Today, you can see the oil refinery across the water, built in the 1970s after the stone industry declined. The quarry was commonly known as Sodom and included both small and large quarry areas.

For long periods, the entire process – from bedrock to finished paving stones – was done on-site. There were only a few small shelters where stonemasons could work during winter.

At times, large-scale quarrying took place, with loading cranes, rail carts and final shaping done in a workshop called Knottfabrik. The ability to ship stone by sea was just as important as finding high-quality granite. The name Lahälla likely means “loading from the rock,” as it had a natural deep harbor.

However, the steep road down to the harbor was challenging. In the beginning, horses had to hold back the heavy stone carts going downhill. Later, trucks were used, but the steep slope was always a nerve-racking part of the journey.

Houses for workers and their families were built around the quarry and near the dock. One apartment building was called Kasern (the Barracks), with rental agreements tied to employment at the quarry. Stone for house foundations was easy to get. The village had a shared laundry house, still standing today by the harbor and several shops served the small but busy community.

The Knottfabrik – A Stone-Cutting Factory

For a long time, stonework was a manual craft. Stonemasons split granite into paving stones using hand tools while standing on gravel-filled wooden boxes. But in the early 1900s, new technology made the process more efficient. In Bohuslän, several factories were built to produce paving stones using machines.

One key machine was the drop hammer, made of cast iron with a hardened chisel at the tip. With great force, it split the granite into smaller pieces. This technique began around 1900. The first drop hammer factory in the Nordic region was built in Hammerodde, Bornholm, in 1902. Another was later opened in Söndrum, Halland. The company Halmstad Stenhuggeri AB gained exclusive rights to sell this patented machine in Sweden and Norway.

To meet high demand, Skandinaviska Granit AB wanted to shift from manual work to industrial production. In 1906, they opened a large factory in Rixö, near Lahälla. It eventually had about 40 machines. Smaller factories followed in Bua, Valbodalen, and Tullboden.

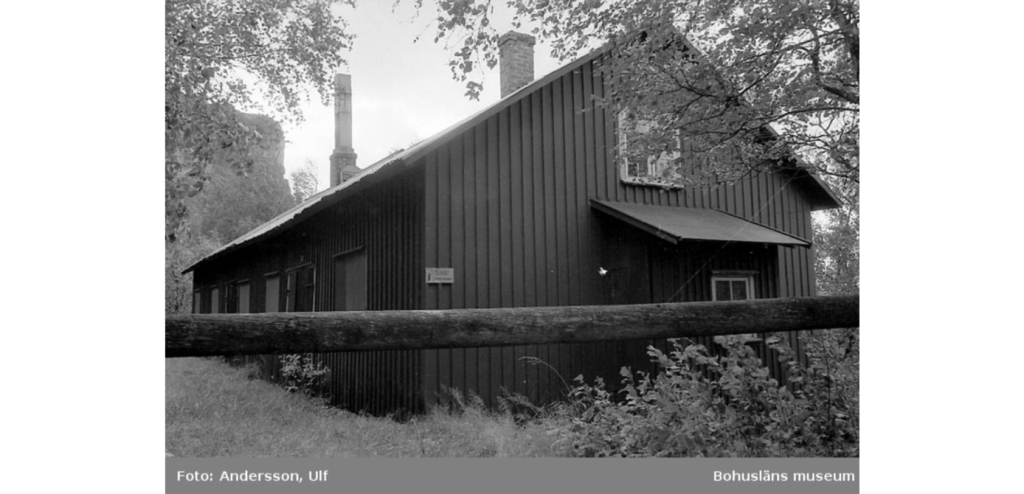

In Lahälla, the Knottfabrik was built around 1920. It had 6 electrically powered drop hammers and splitting machines. The building was placed on a slope to make the work process smoother. Granite slabs were brought in at the top and fed into the machines by workers. The stones were positioned carefully to produce the best paving stones.

The drop hammer struck the granite, and the small blocks (called knott) fell into steel baskets. Waste material was separated through a side chute. Good paving stones slid down to the floor below, where they were loaded onto wagons for shipping. A rail track system was used on the bottom floor to move the stones.

Ventilation came through small openings in the walls. The work was dangerous. Old stonemasons recalled that the local doctor had never seen as many hand injuries as during the time of the Knottfabrik.

Sodom – The Quarry with a Biblical Name

The granite quarry in Lahälla is commonly known as Sodom – the name even appears on maps. In the Bible, Sodom is described in the Book of Genesis as a sinful city, destroyed by God as punishment. Many hardened sinners perished in the disaster.

Why the quarry got this name is unclear, but we can guess. Perhaps the quarry, visible from far across the water, looked like a ruined city with all its broken rock and stone debris – like a place struck by lightning from the sky. Or perhaps the name was a joke, reflecting how the religious locals on nearby Stångenäset viewed the incoming stoneworkers.

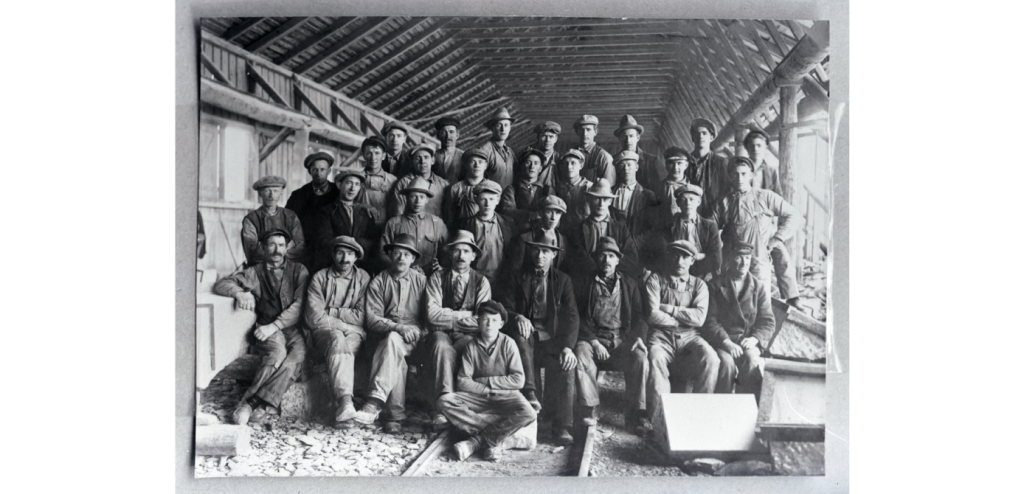

These new workers were often seen as sinners – they rarely went to church and were not always involved in traditional religious practices like confirmation or household catechism. But instead of religion, the stone industry in Bohuslän became a cradle of the modern labor movement. Early unions formed here, and the first cooperative stores were opened. People read socialist thinkers like August Palm, Axel Danielsson, and Hinke Berggren more than the Little Catechism.

Hinke Berggren, a socialist speaker who promoted the right to use birth control, even visited quarry towns in Bohuslän, giving speeches and selling “rubber goods” during his meetings. It’s no wonder the churchgoers were shocked.

Since the 1960s, no stone work has taken place here in Lahälla. The quarry is now quiet, filled with trees like aspen and birch that grow between the piles of leftover stone. The dramatic landscape, the colors and the silence give the feeling of an ancient ruined city—full of mystery and stories.

The Stonemason Created Jobs for Many

It wasn’t just stonemasons who worked in and around the quarry – many others were also needed to support the industry. Even during the early days of small-scale quarries, a blacksmith’s workshop was essential. Stonemasons regularly brought their tools – i.e. chisels, wedges and crowbars – to be sharpened or repaired.

Other workers installed and maintained equipment like cranes, metal structures, rail tracks, carts and machines.

Just off the access road, you can still see the stone dam and a simple concrete base – these are the only remains of the old workshop building, which burned down (exact date unknown). This was where the blacksmiths worked, keeping tools in good condition. They had access to an electric bellow, and behind the workshop was a cooling pond, which still remains today.

The workshop also housed an electric compressor used for pneumatic drills, a small carpentry shop, and a canteen for the workers. Around the quarry area, there were also storage buildings and cart sheds which are also gone today – except for the dam. However, some of these buildings can still be seen in photos from the 1970s.

There was also a transformer station, which played a key role in supplying electricity to both the Knottfabrik and the workshop. It converted power from the main electrical grid to the correct voltage levels needed for the factory machines.

In the Beginning of Time: The Precambrian Bedrock and Bohuslän Granite

In the dawn of time, during the so-called Precambrian era, layers of bedrock were formed deep within the Earth. In Scandinavia, gneiss dominates as the primary bedrock type, though granite is also common—more so than one might think. However, granite only appears at the surface in certain limited areas, meaning it is visible without the need for deep open-pit mining.

One such area is in Bohuslän, stretching from Stångenäset in the south up to Grebbestad in the north. This granite belt then continues inland through the Bullar region and reaches all the way to Idefjorden, where some of the most renowned quarries are found.

Granite is the youngest of all bedrock types in the region, having formed approximately 900 million years ago. The word “granite” itself derives from the Latin word granum, meaning “grain.” The rock is composed of grains—mainly quartz, mica, and feldspar. This mineral mix can vary from place to place; so can the grain size. Additionally, the presence of other minerals can influence the rock’s color. For example, the famous red Bohus granite owes its hue to the presence of potassium feldspar.

However, not all Bohus granite is red. In Lahälla, for instance, both red and grey varieties can be found. Granite is hard, dense, and typically free of fractures, making it well-suited for quarrying, shaping, and even polishing. In some cases, the effects of natural weathering—wind and rain over millennia—have created smooth, even surfaces in the bedrock. One such example can be seen in the rock outcrop on Hållö Island, where the granite has been naturally polished over time.

That said, quality can vary. Many of the now-abandoned quarries in Bohuslän, such as Sodom in Lahälla, were closed because the stone quality declined at greater depths. High-quality granite should weigh around 2800 kg per cubic meter, indicating a high density. The presence of intruding rock veins, such as diabase, can also reduce the desirability of a granite deposit.

When these diabase veins break through to the surface, they are colloquially known as “Hin Håle’s harrow tracks”—a colourful local expression, referring to the Devil’s handiwork.